Brief introduction to reverse engineering for CTF (using radare2 + angr)

Intro

I’m writing this blog in order to give a brief introduction of reverse engineering applied to CTFs. Actually I’am not able to write complex sentences in english tongue, then I will keep it short giving only the basic information, in fact this blog is more an exercise to me than a real blog article for you.

Requirements

- Basic binary analysis understanding (assembly, CFG)

- radare2, angr are required in order to follow the steps described here below

Start

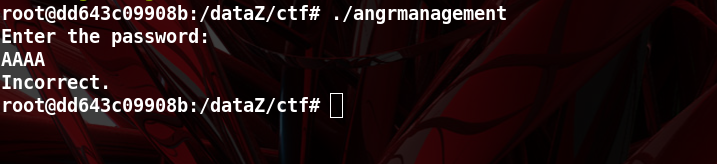

We have the following binary file: angrmanagement

We suppose that the binary file runs remotely, then we can’t apply the patching/debugging stuff.

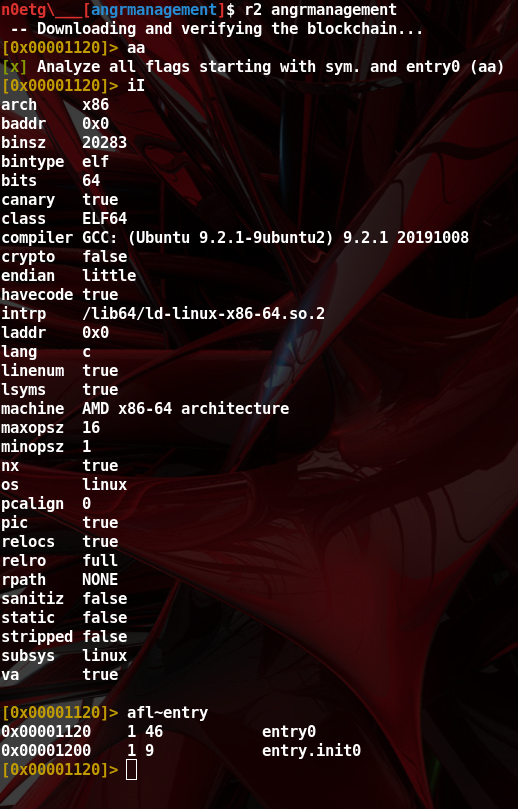

- Giving some basic static analysis here, r2 cheatsheet here

- “

aa” : analyzing the binary: disassembly, construct CFG, imported functions, etc. - “

iI” : prints out binary information - “

afl~entry” : list functions and grep on line row (~) containing ‘entry’ string

- “

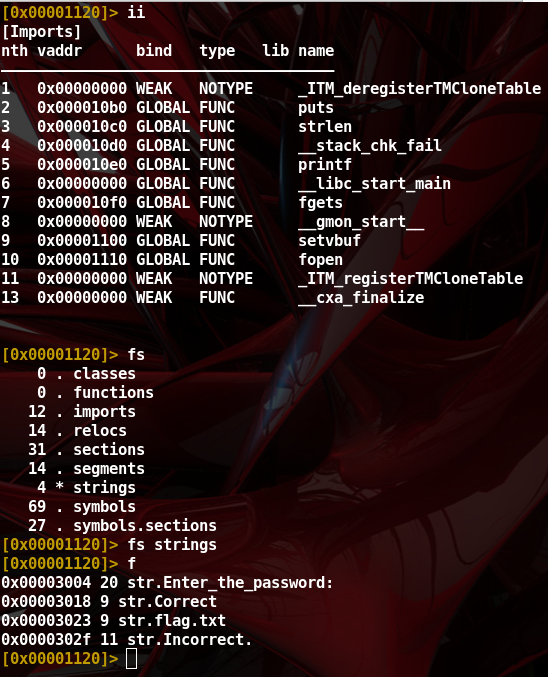

- List functions imported by the binary and printable strings

- “

ii” : list binary’s function imported - “

fs strings” : select strings name space - “

f” : print name space selected

- “

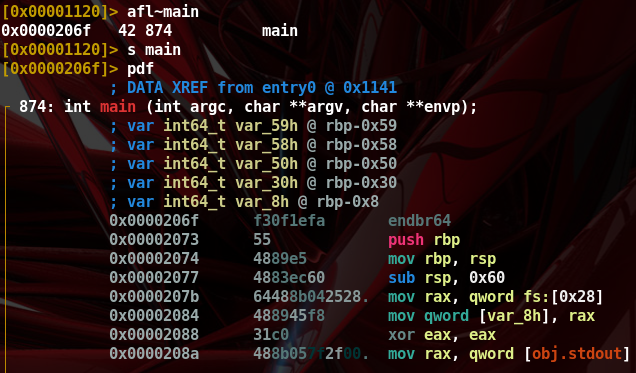

- Nothing suspicious. We inspect the function ‘main’

- “

s main” : Seek to main - “

pdf” : disassemble function

- “

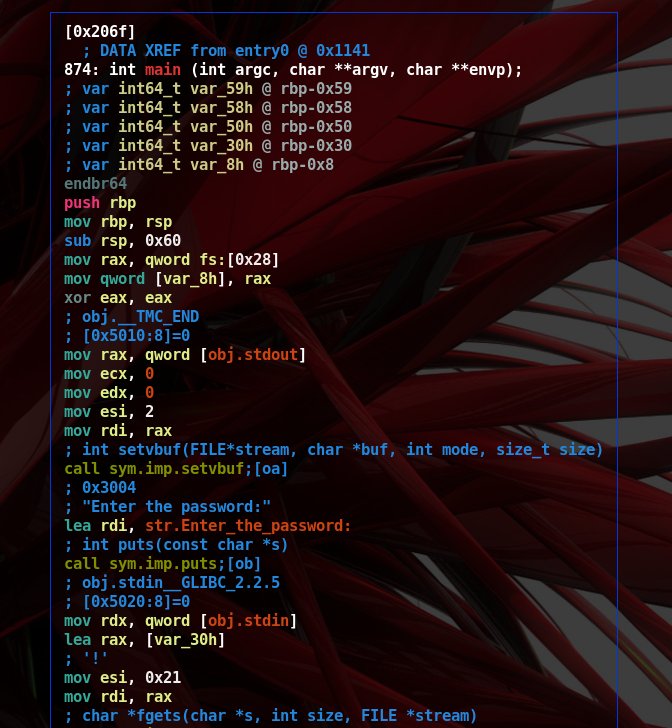

- By getting the control flow graph (CFG) we understand the assembly instructions from the point of view of basic blocks (nodes) and control flow (edges). For more context:

- Basic block is a blob of assembly instructions ending in a Change of Flow Instruction (COFI), such as jmp, call, and ret.

- CFG links together those basic blocks by constructing the control flow path

- Control flow executed (CFE) is a subset of the CFG and refers to a control flow captured during the execution of the binary

- To show CFG in r2 we type “

VV” that stands for visual graph mode- Moving on the graph requires to use arrow keys or ‘h’,’j’,’k’,’l’ if you’re familiar with vim

- By inspecting the binary’s strings we find out the program asking to insert a password. We save the information and go further.

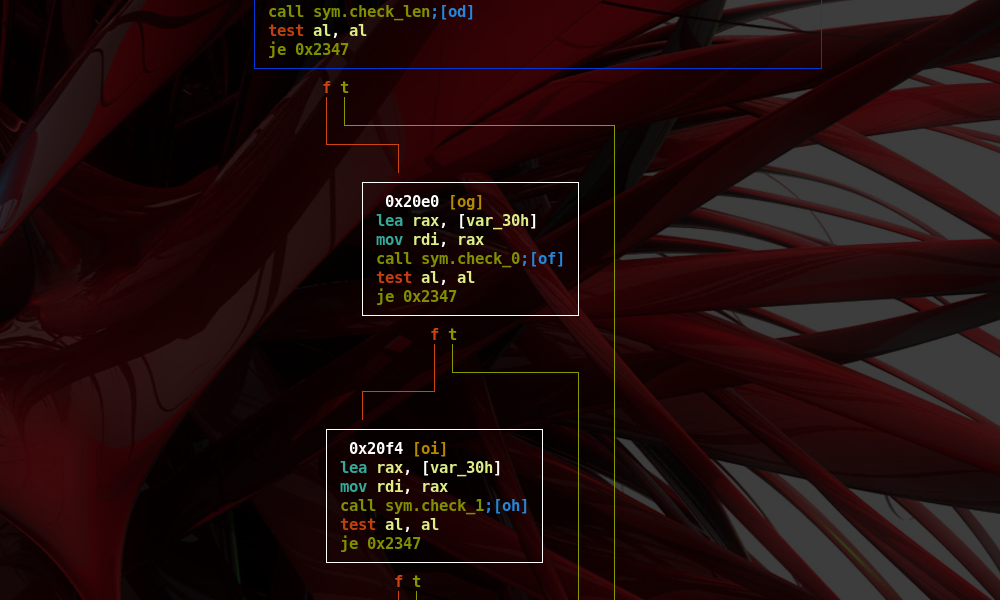

- Following the control flow we find calls to functions such as ‘sym.check_1’

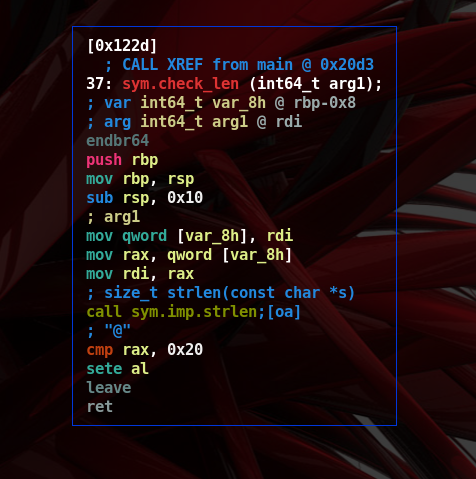

- Going back to graph mode gives more details on the ‘sym.check_len’ function.

- Type “

od” to traverse a function called from the basic block selected, - Type “

?” to list commands that can be invoked in graph mode

- Type “

- Here we note the instruction

cmp rax, 0x20changing the status of the register EFLAGS- After that, instruction

sete alwill set registeralto 1 if the EFLAGS’s zero flag was 0 - We conclude the password has to be 0x20 byte long

- Type “

x” and then the enter key to go backward in graph mode

- After that, instruction

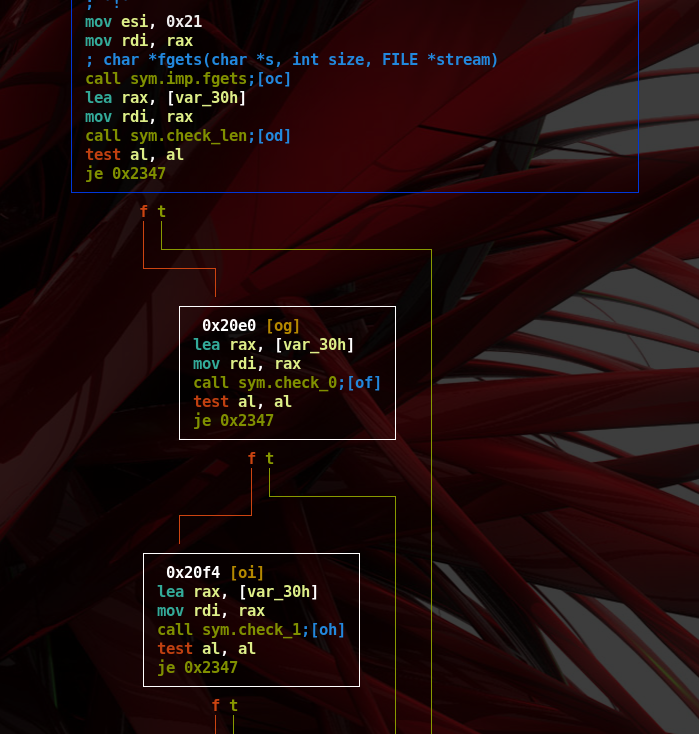

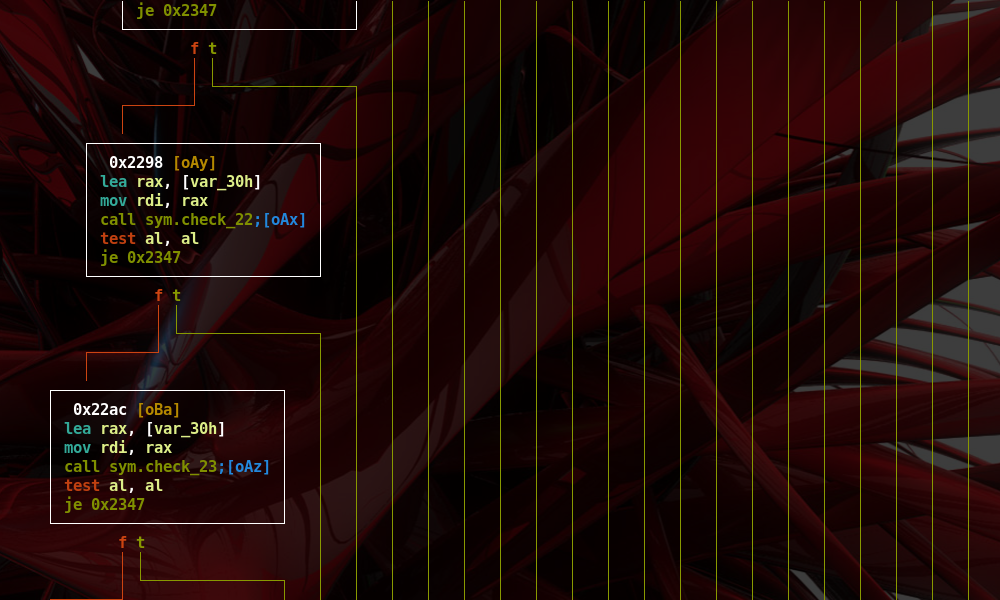

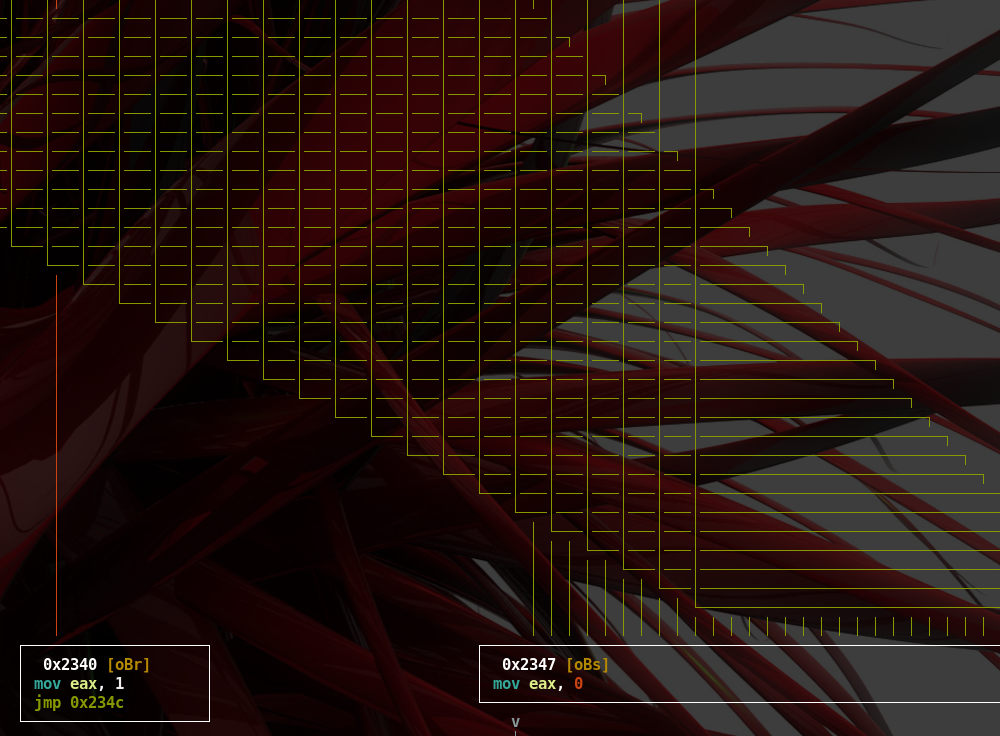

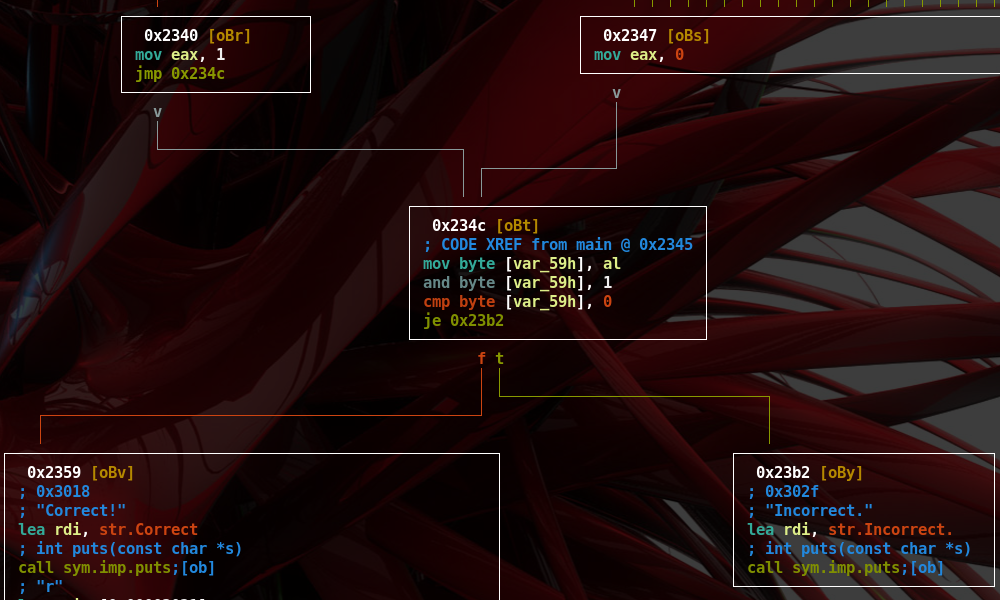

- As can be seen in figure below, each basic block calls a function to check some type of information regarding the input (e.g. ‘sym.check_1’, ‘sym.check_2’, and so on)

- If a check fails its return value, which is saved in RAX register, will be a different value than the 0 one.

- As we can note the last compare prints the content of the ‘flag.txt’ file.

- All checks previously shown should return true

- We start reversing

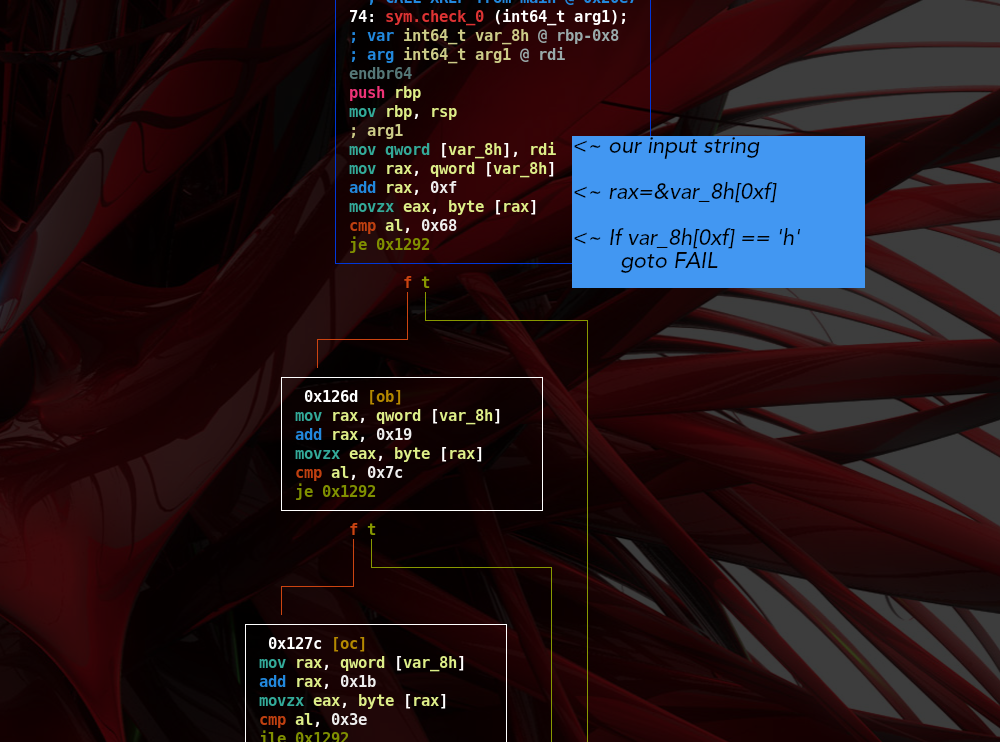

check_0function-

The function does check that: ` input[15] != ‘h’ and input[25] != ‘ ’ and input[27] != ‘>’ `

-

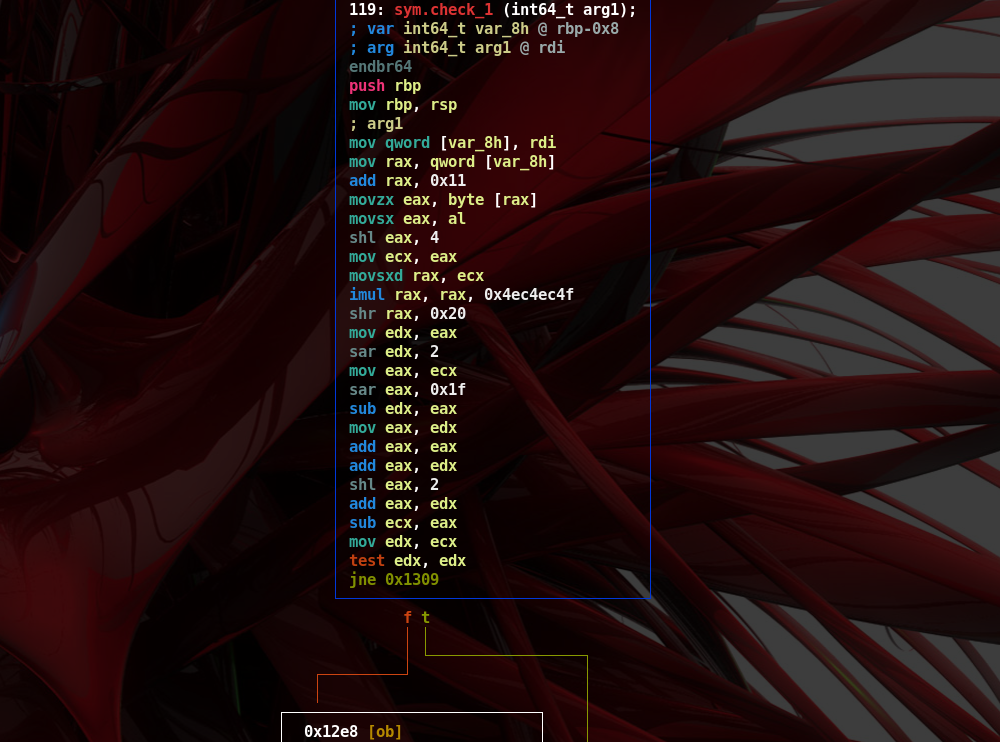

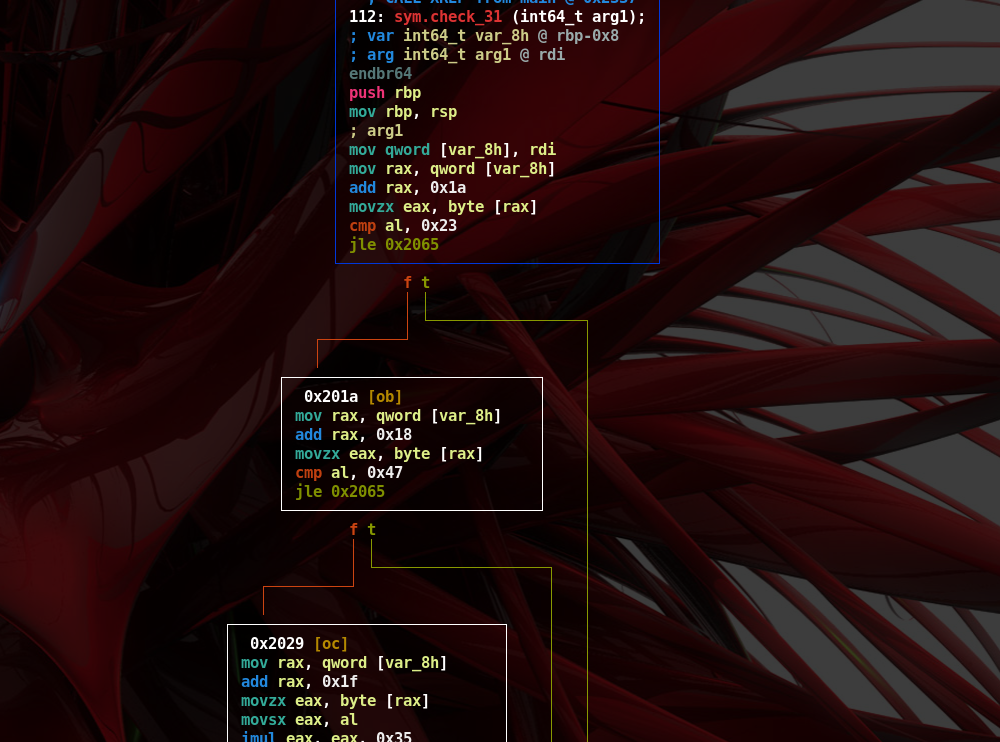

- The “check” functions start to get a little obfuscated starting from the

check_1one- 31 check functions are present

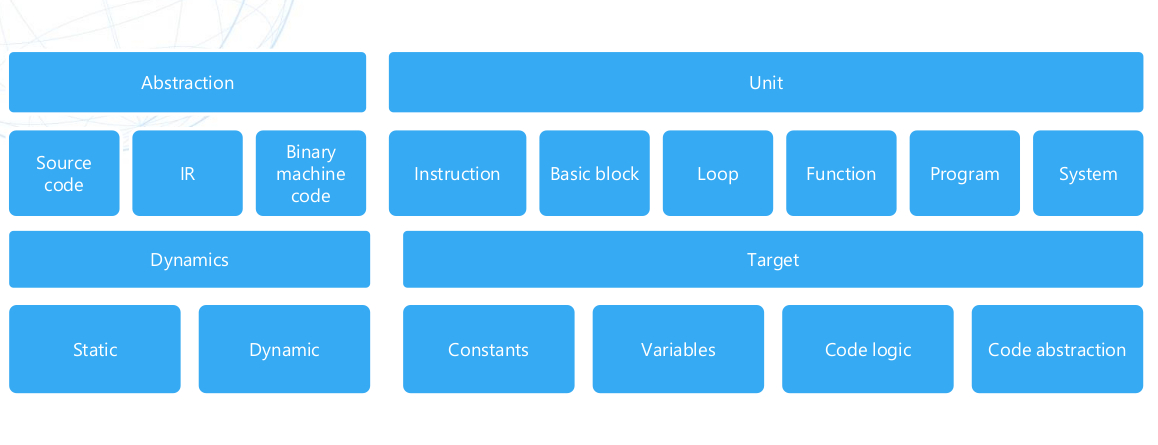

- After inspecting some of the check functions we give a quick look at the following image illustrating taxonomy of binary obfuscation

- The check functions use encode literals and arithmetic types of obfuscation.

- Dataflow analysis techniques can be used to solve the problem

- Also symbolic execution can be used, if we have control of the paths to be traversed and so the path grow

-

To limit the path grow during symbolic executiong, we end up with the following considerations:

- The string/our input have to be 32 byte long, the input is saved at rbp-0x30 address of main function’s stack

- Avoid to jump the offset 0x2347, and instead follow the path to reach 0x2359 offset

- The instruction

je 0x2347is 6 byte long, and after each of them, there’s a basic block that we want to match in our path - The instruction

endbr64must be patched/hooked because breaks angr (more here) - main() function is located at 0x206f offset

- We write down some python code in order to simplify the considerations 2,3,4,5; (utils.py); We could do that in angr as well.

import r2pipe

import re

class r2Ctf(r2pipe.open_sync.open):

def __init__(self, binary_name, symbols=[]):

super(r2Ctf,self).__init__(binary_name)

self.binary_name = binary_name

self.symbols = symbols

self.__init_obj()

def __init_obj(self):

self.cmd('aa')

self.offsets=dict()

self.offsets['find'] = [0x2359] #+ [ x["offset"] + x["len"] for x in self.cmdj('/aaj je 0x2347') ]

self.offsets['avoid'] = [0x2347]

self.offsets['patch'] = [(0x1fff,4)] + [ (x["offset"], x["len"]) for x in self.cmdj('/aaj endbr64') ]

for x in self.cmdj('aflj') :

match = x['name']

rets = re.search("^sym\.imp\.(.*)$", match)

if rets :

match = rets.group(1)

if match in self.symbols :

self.offsets[match] = x["offset"]

def __str__(self):

return "Binary: {}\n".format(self.binary_name)- read the comments in the code (docs)

import angr

import claripy

import utils

proj_name = "angrmanagement"

binary = utils.r2Ctf(proj_name, symbols=["main", "fgets"])

# Initialize Project, generate CFG

proj = angr.Project(proj_name, auto_load_libs=False)

# Get base address from virtual loader

main_obj = proj.loader.main_object

base_address = main_obj.min_addr- The symbolic execution in angr is composed of one ‘SimulationManager’ object and many ‘SimState’ that we have by traversing basic blocks.

- A state gives access to its registers and memory

- To hook something in angr we need to define a method accepting a state object as argument

# define the method template to hook something

# - set rax to 0, that is return value

# - simulate the epilogue function to return to the caller function (works only in stdcall standard)

def ret0_x64(state):

state.regs.rax = 0

state.regs.rip = state.mem[state.regs.rsp].uint64_t.resolved

state.regs.rsp = state.regs.rsp + 8

# patch with nops template method

def ret_nops(state):

pass- Map as symbolic variable the address where’s the input saved

- We do that by hooking fgets call from main function, and get the address of the buffer from RDI register

user_arg = claripy.BVS("user_arg", 0x20*8) #*

flg_add_constraints = False

def add_constraints(state, user_arg) :

for byte in user_arg.chop(8):

state.add_constraints(byte >= ' ') # \x20

state.add_constraints(byte <= '~') # \x7e

state.add_constraints(byte != 0) # NULL

def inject_symbol(state):

global user_arg

buffer_addr = state.regs.rdi

print("Buffer:", buffer_addr)

state.memory.store(buffer_addr, user_arg)

if flg_add_constraints :

add_constraint(state, user_arg)

return utils.ret0_x64(state)

# Here we hook/patch

hooks = [ (base_address + x, utils.ret_nops, length) for x,length in binary.offsets['patch'] ]

for x, ff, y in hooks:

if (x - base_address) == binary.offsets["fgets"] :

proj.hook(x, inject_symbol)

else :

proj.hook(x, ff, length=y)- Start symbolic execution

state = proj.factory.entry_state(addr=base_address+binary.offsets['main'])

simgr = proj.factory.simulation_manager(state)

# Maybe this will take time, in any case limit memory usage

simgr.explore(find=[base_address+x for x in binary.offsets['find']], avoid=[base_address+x for x in binary.offsets['avoid']])

password = simgr.found[0].solver.eval(user_arg, cast_to=bytes)

print("Password: {}".format(password))

proc = subprocess.Popen("./angrmanagement", stderr=subprocess.PIPE, stdin=subprocess.PIPE, stdout=subprocess.PIPE)

stdout, stdin = proc.stdout, proc.stdin

stdin.write(password + "\n")

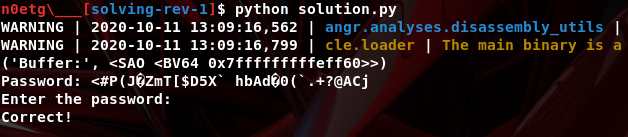

print( "".join(stdout.readlines()) )-

After executing solution.py, utils.py we have the password:

’

<#P(J\xb9ZmT[$D5\x06X` hbAd\x880(`.+?@ACj’